Why do people lie (or rather: lie so little)

In our research paper on which this website is based, we also study why people lie, or rather: why people lie so little.

Many ideas have been suggested to explain the behavior in the die-rolling or coin-tossing experiments. In our paper, we formalize all of these ideas, i.e., we build mathematical models that capture the intuitive ideas suggested. The classes of models we consider cover three broad types of motivations: a direct cost of lying (e.g., Ellingsen and Johannesson 2004, Kartik 2009); a valuation of some kind of reputation linked to the report (e.g., Mazar et al. 2008); and the influence of social norms and social comparisons, including guilt aversion (e.g., Weibull and Villa 2005, Charness and Dufwenberg 2006).

We also consider numerous extensions, combinations and mixtures of the aforementioned models (e.g., Kajackaite and Gneezy 2015, Boegli et al. 2016) including several new models that, to us, seemed plausible. For all models we make minimal assumptions on the functional form and allow for full heterogeneity of preference parameters, thus allowing us to derive very general conclusions.

The literature is not very good at distinguishing between these models. As a consequence, the meta study can also be explained by many different motives.

One of the key insights of our research paper is identifying four empirical tests that can differentiate between the models. We show that the models differ in (i) how the distribution of true states affects one’s report; (ii) how the belief about the reports of other subjects influences one’s report; (iii) whether the observability of the true state affects one’s report; (iv) whether some subjects will lie downwards, i.e. report a state that yields a lower payoff than their true state, when the true state is observable.

We take a Popperian approach in our empirical analysis (Popper 1934). Each of our tests, taken in isolation, is not able to pin down a particular model. However, each test is able to cleanly falsify whole classes of models and all tests together allow us to tightly restrict the set of models that can explain the data. Since we formalize a large number of models, covering a broad range of potential motives, the set of surviving models is more informative than if we had only falsified a single model, e.g., the standard economic model. The surviving set obviously depends on the set of models and the empirical tests that we consider. However, the transparency of the falsification process allows readers to easily adjust the set of non-falsified models as new evidence becomes available.

In the research paper, we then conduct new laboratory experiments with more than 1600 subjects to test between the classes of models.

To test the influence of the distribution of true states (test (i)), we let subjects draw from an urn with two states and we change the probability of drawing the high-payoff state between treatments. Our comparative static is 1 minus the ratio of low-payoff reports to expected low-payoff draws. Under the assumption that individuals never lie downwards, this can be interpreted as the fraction of individuals who lie upwards.

We find a very large treatment effect. When we move the share of true high-payoff states from 10 to 60 percent, the share of subjects who lie up increases by almost 30 percentage points (see below). This result falsifies direct lying-cost models because this cost only depends on the comparison of the report to the true state that was drawn but not on the prior probability of drawing the state.

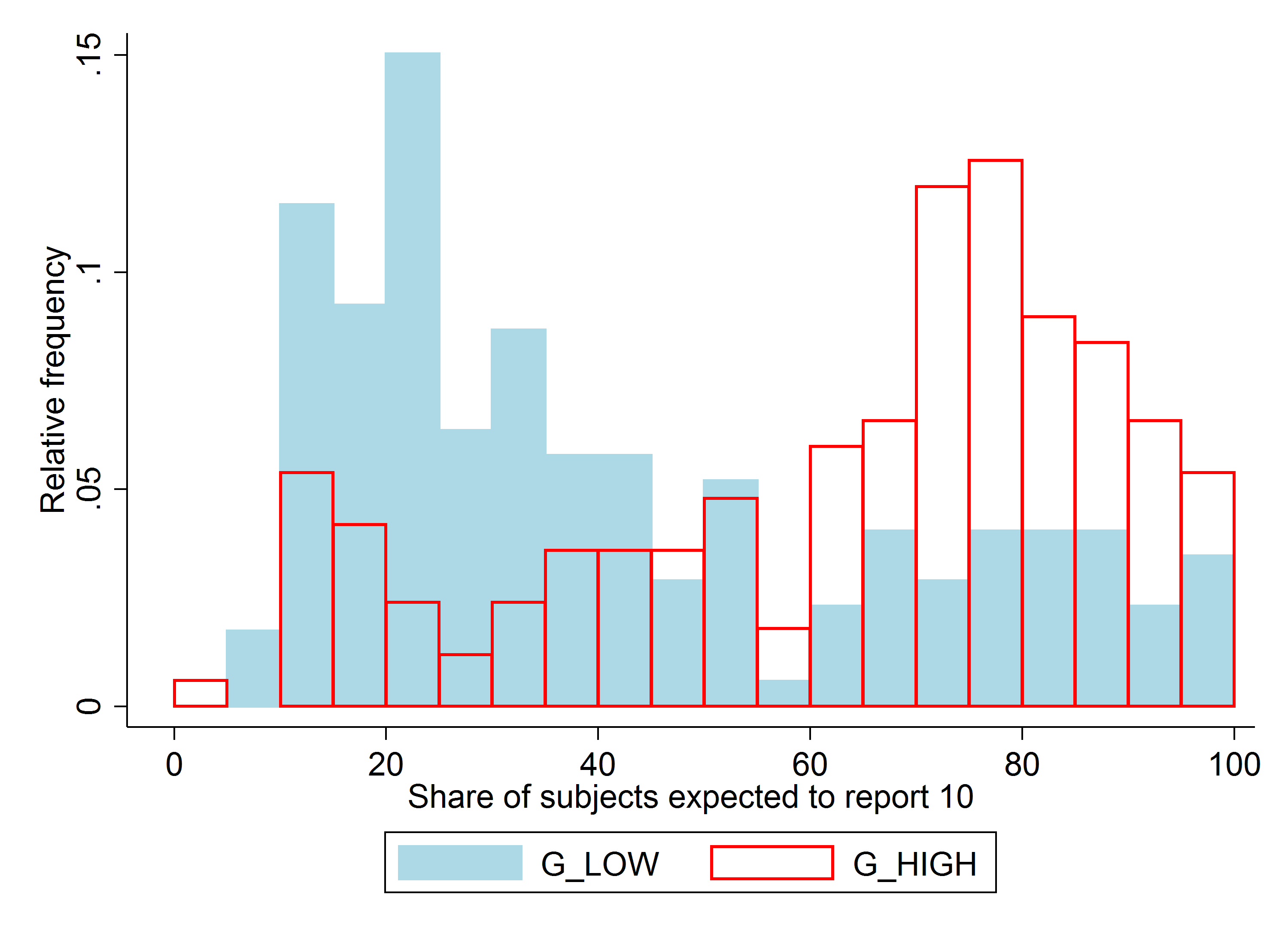

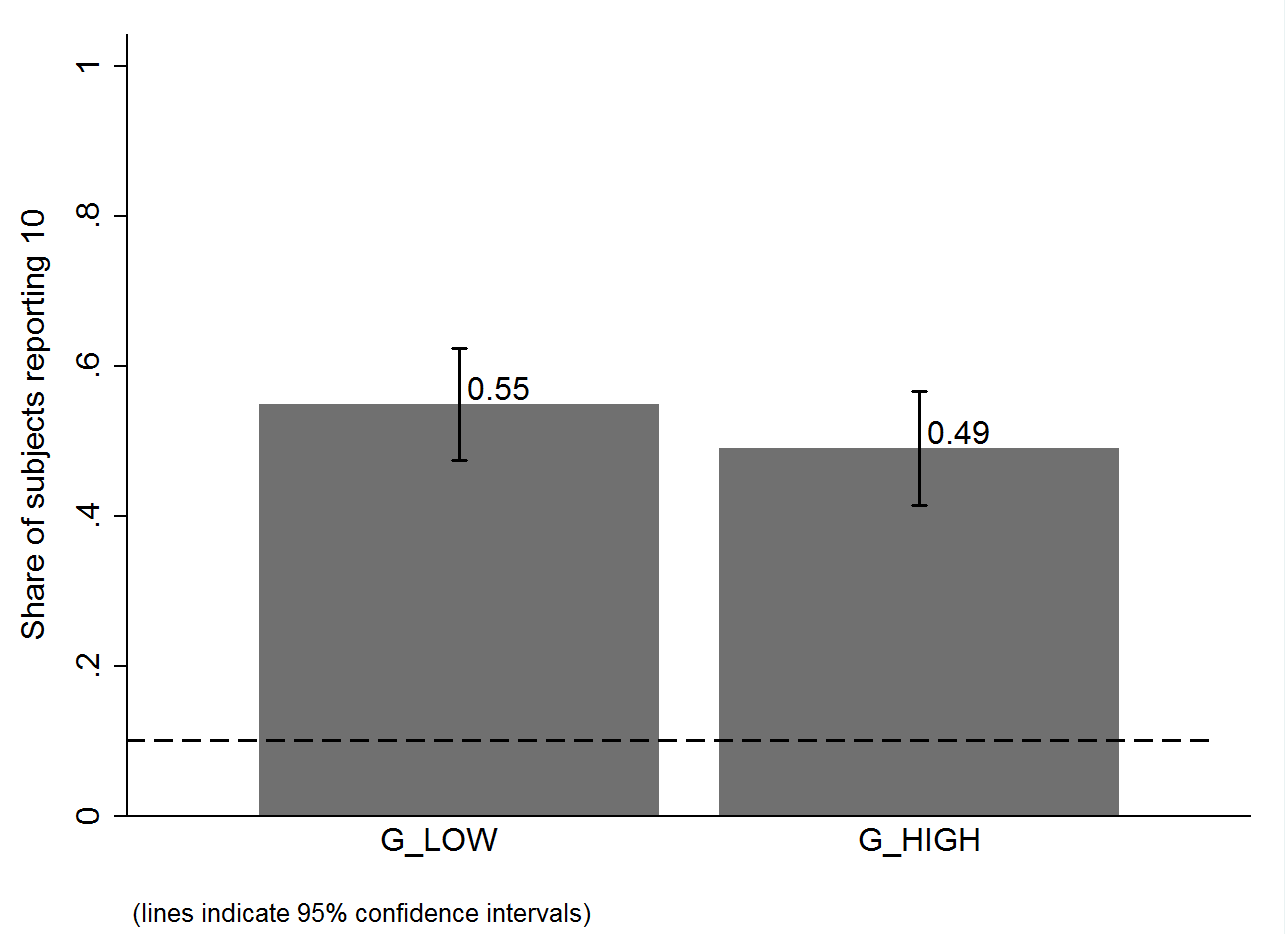

To test the influence of subjects’ beliefs about what others report (test (ii)), we use anchoring, i.e., the tendency of people to use salient information to start off one’s decision process (Tversky et al. 1974). By asking subjects to read a description of a “potential” experiment and to “imagine” two “possible outcomes” which differ by treatment, we are able to shift (incentivized) beliefs of subjects about the behavior of other subjects by more than 20 percentage points (see below, left graph).

This change in beliefs does not affect behavior: subjects in the high-belief treatment are slightly less likely to report the high state, but this is far from significant (see below, right graph). This result rules out all the social-comparisons models we consider. In these models, individuals prefer their outcome or behavior to be similar to that of others, so if they believe others report the high state more often they want to do so, too.

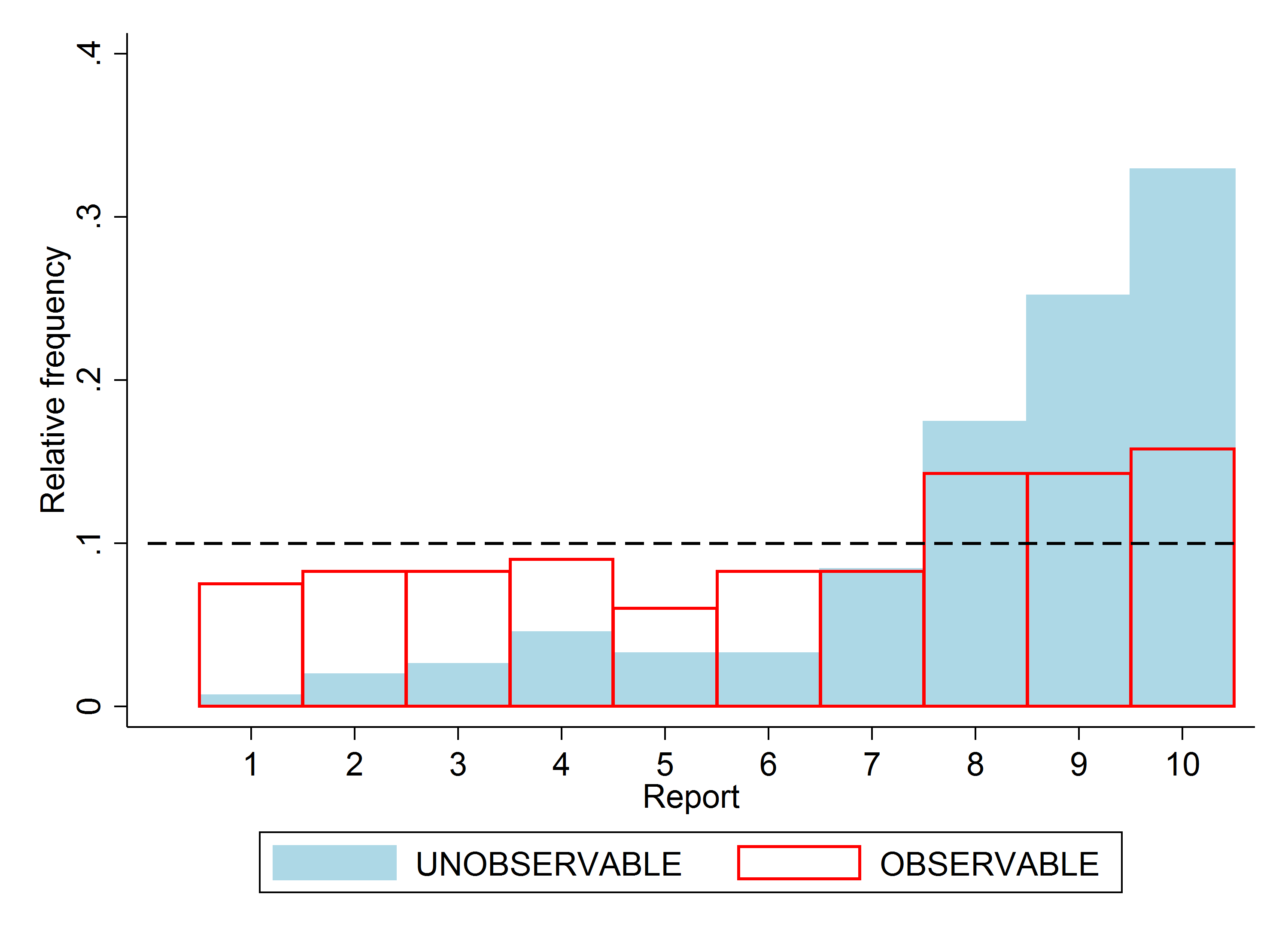

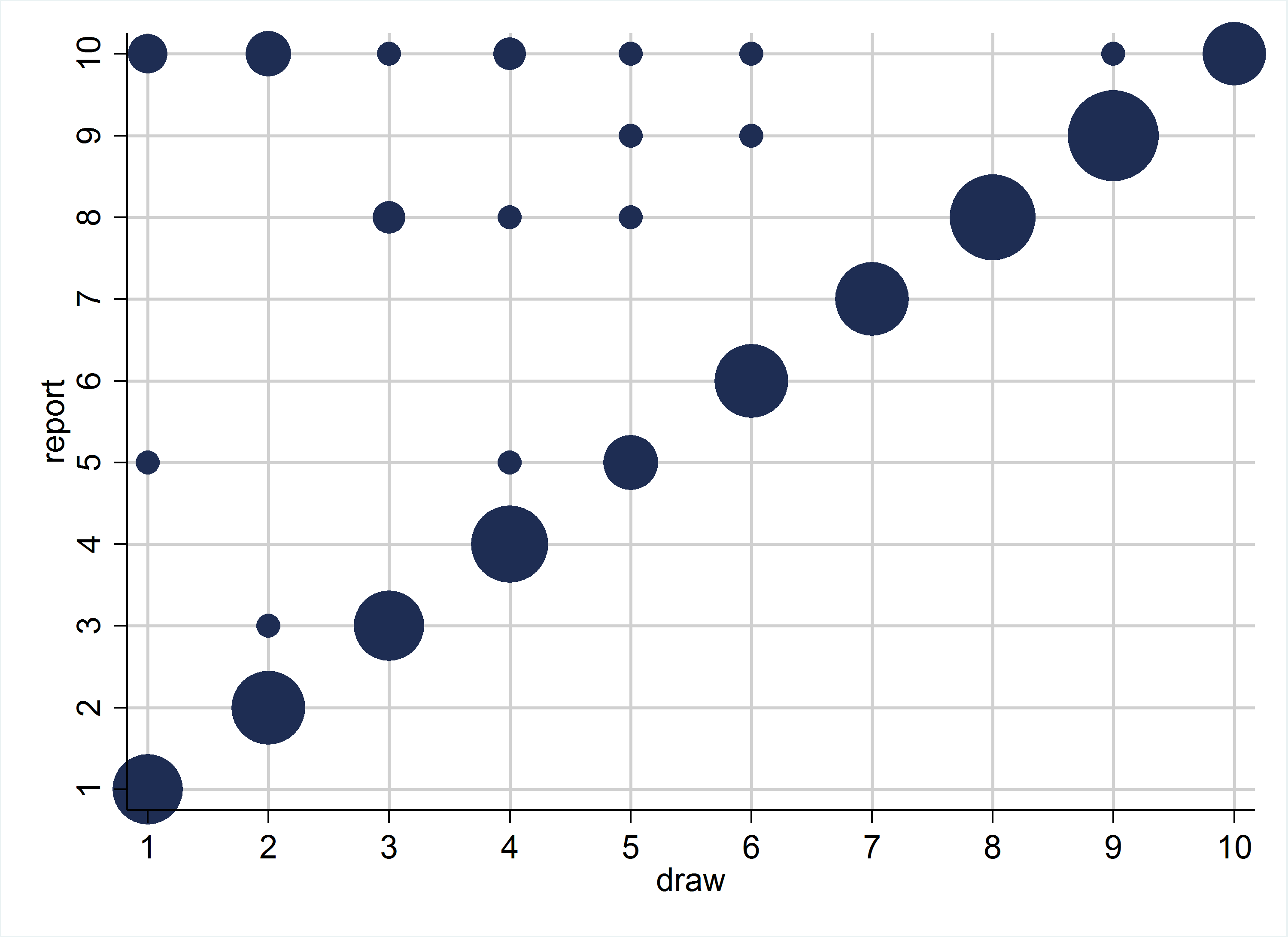

To test the influence of the observability of the true state (test (iii)), we implement the random draw on the computer and are thus able to recover the true state. We use a double-blind procedure to alleviate subjects’ concerns about indirect monetary consequences of lying, e.g., being excluded from future experiments. We find significantly less over-reporting in the treatment in which the true state is observable compared to when it is not (see below).

Moreover, we find that no subject lies downwards in this treatment (test (iv), see below). These findings are again inconsistent with lying-cost models and social-comparison models since in those models utility does not depend on the observability of the true state.

At the end of the research paper, we compare the predictions of the models to the gathered empirical evidence. The main empirical finding is that our four tests rule out almost all of the models previously suggested in the literature. From the set of models we consider, only combining a preference for being honest with a preference for being seen as honest (or a model whose intuition and prediction are very similar) can explain the data.

This intuition is also present in the concurrent papers by Khalmetski and Sliwka (2016) and Gneezy et al. (2016). We then turn to calibrating a simple version of our model, showing that it can quantitatively match all the stylized facts we uncovered in the meta study and the patterns in our new experiments. In the model, individuals suffer a cost that is proportional to the monetary gain from lying and a cost that is linear in the probability that they lied (given their report and the equilibrium report). Both cost components are important.

Three key insights follow from our study. First, our meta analysis shows that the data are not in line with the assumption of payoff-maximizing reporting but rather with some preference for truth-telling. Second, our results suggest that these preferences are comprised of two components, a direct cost of lying that depends on the comparison between the report and the true state, and a reputational cost for being thought of as a liar. This contrasts with most of the previous literature on lying aversion which focuses on a single cost component. Finally, policy interventions that rely on voluntary truth-telling by some participants could be very successful, in particular if it is made hard to lie while keeping a good reputation.

In this study, we focus exclusively on the die-rolling or coin-tossing experiment due to Fischbacher and Föllmi-Heusi (2013). This experimental paradigm is, however, not the only laboratory experiment that is used to study honesty and lying. The die-rolling experiment itself is related to Batson et al. (1997) and Warner (1965). Three other paradigms are widely used in the literature.

In the sender-receiver game, introduced by Gneezy (2005), one subject knows which of two states is true and tells another subject (truthfully or not) which one it is. The other subject then chooses an action. Payoffs are determined by the state and the action. The advantage is that the experimenter knows the true state and can thus judge individually whether a subject lied or not. The strategic interaction makes the setting more complex though, especially if one is interested in studying the underlying motives of reporting behavior.

In the “matrix task”, introduced by Mazar et al. (2008) (and similar real-effort reporting tasks, e.g., Ruedy and Schweitzer (2010)), subjects solve a mathematical problem, are then given the correct set of answers and report how many answers they got right. Finally, they destroy their answer sheet, making lying undetectable. This setup is quite similar to Fischbacher and Föllmi-Heusi (2013) but has the advantage of being less abstract. It does add ambiguity about the truthful proportion of correct answers in the population which makes testing theories harder.

In Charness and Dufwenberg (2006), subjects can send a message promising (or not) a particular future action. Incorrect messages can thus be identified for each subject ex-post. Charness and Dufwenberg show that the message affects the action, the truthfulness of the message at the time of sending is thus unclear. Other influential experiments in this literature are, e.g., Ellingsen and Johannesson (2004) and Vanberg (2008).